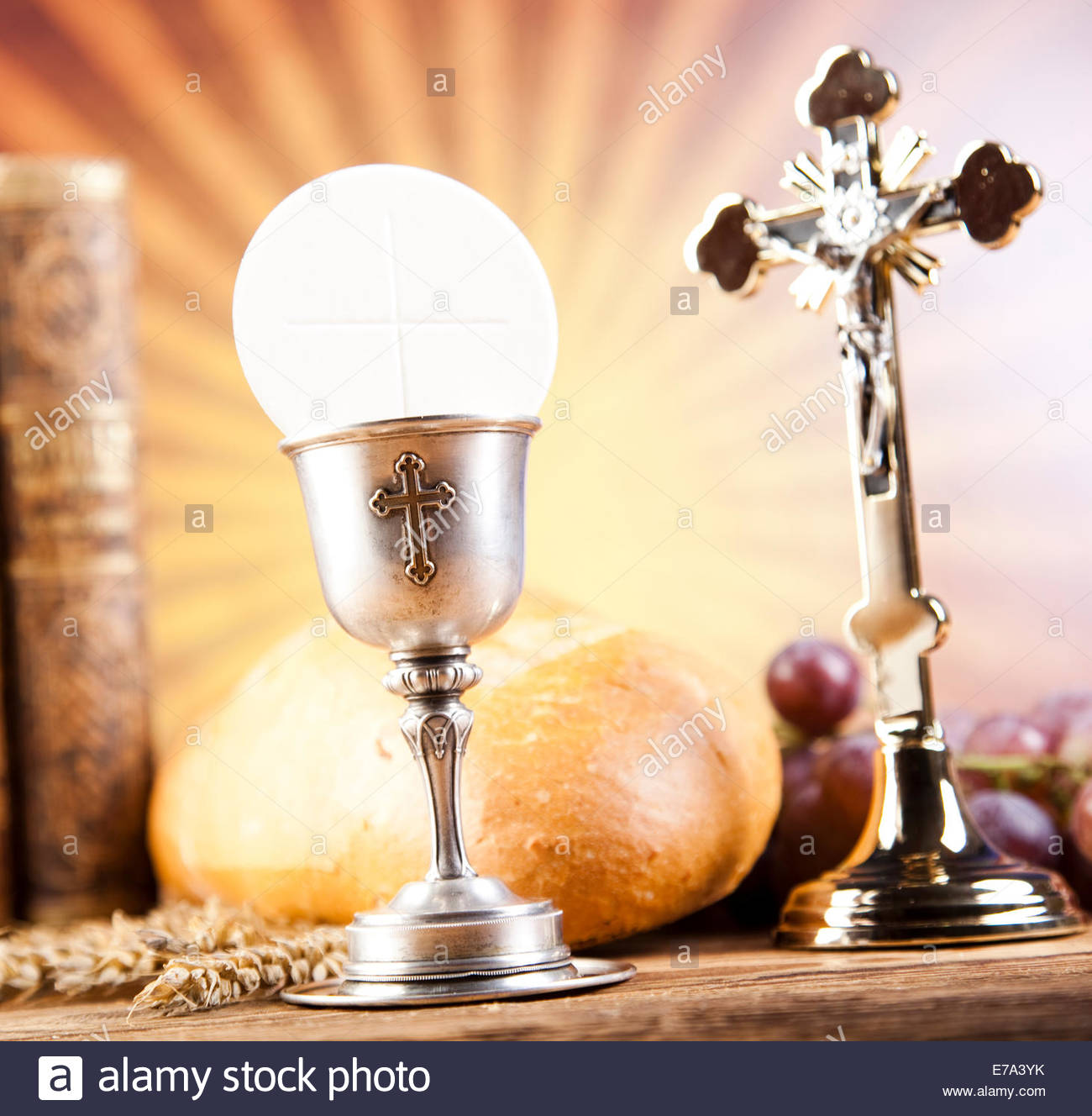

Whatever we call it – the eucharist, mass, holy communion, the Lord’s Supper – it’s at the heart of Christian life together. Eating bread – or a wafer – and drinking wine – or non-alcoholic grape juice – is at the very least a family meal. Depending on our church tradition, it might be more than that. Catholics believe the bread and wine become the body and blood of the Lord Jesus Christ in a literal sense. Protestants generally don’t, but they have quite a broad view of what happens at communion, all the way from a kind of ‘real presence’ to seeing the bread and wine as simply a memorial.

But whatever we believe about communion, it’s a very significant thing. In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul says: ‘Everyone ought to examine themselves before they eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For those who eat and drink without discerning the body of Christ eat and drink judgment on themselves. That is why many among you are weak and sick, and a number of you have fallen asleep’ (1 Corinthians 11: 28-30).

In some churches this has been taken to mean communion should be a rare and special event, celebrated perhaps only once a year and preceded by fasting and confession. For others, it’s a routine part of worship celebrated every Sunday.

Either way, it is a gift and a blessing to the Church. But is it ever right for believers not to take communion? The answer is very challenging. According to Scripture, there is only one reason not to take part in the family meal, and that is when family relationships have broken down. In other words, if we are in a state of unresolved conflict and unforgiveness with a brother or sister in Christ.

Paul says: ‘So then, whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of sinning against the body and blood of the Lord’ (1 Corinthians 11:27). It’s easy to take this as referring generally to sinfulness and sinful acts. But in context, that’s not what it means. Paul has been talking to the Corinthians about their relationships and criticising the divisions among them. It was not a happy church. So when he talks about bringing judgment on themselves because they don’t discern the body of Christ, it isn’t the bread of communion he’s talking about, but the church. When we are angry, jealous, neglectful or contemptuous of a fellow-believer at communion, we are eating and drinking in an unworthy manner.

This is a great challenge to us, because it means we are responsible for being reconciled with our neighbours before we take communion. Jesus hints at this in the Sermon on the Mount: ‘Therefore, if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there in front of the altar. First go and be reconciled to that person; then come and offer your gift’ (Matthew 5:23).

It is also a great comfort, because it means there is room at the table for sinners. That doesn’t mean we should be easy about serious, unconfessed sin – arguably, that is itself a breach of Christian fellowship, even if no one else knows about it, because we are accountable to one another. But it means that while we should always examine ourselves and be penitent for what we’ve done wrong – and particularly at communion – we don’t have to reach a particular standard of righteousness before we can eat bread and drink wine. When we share a meal with our ordinary family, we can look round the table and know everyone’s faults – but we know we are loved and accepted anyway, and it’s the same with communion. The bread and wine speak of Christ dying to bring us into God’s family, and he wants us to join him at his table.